Out of all the many personal projects I’ve started these days, one over-arching project is learning how to live without Google and its many myriad services. Google’s search, maps and email are the most widely known. Google’s trying to get into The Social via Google+, and it’s established a nearly unassailable position in mobile (smart phone and tablet) operating systems with Android. Google’s stock market valuation is in the hundreds of billions and its quarterly earnings are in the tens of billions. Google has the resources to hire the best and brightest and to keep them. It refines what it has and is trying to develop new areas for future expansion, such as AI, robotics, and home automation (see Nest acquisition). Its offerings are broad, deep, and refined.

The problem is the cost to use these goods and services, and that’s Google’s increasingly invasive collection of personal information. In the past I tended, like a frog in a slowly heating pot, to not pay too much attention to the loss of my personal privacy and information as the cost of using these goods and services “for free.” All that changed with the NSA revelations, and the realization that no matter how much Google, Facebook, Microsoft et el righteously complain, they helped the NSA by providing methods, tools, and eventually that same personal information. I know that NSA is trolling for far more information, such as cellular phone metadata, but there would be no metadata (or data in general) if it wasn’t collected by commercial interests in such detail in the first place.

With that background, I’ve been looking at open source tools and alternative services to slowly replace what Google currently offers. In order to make this work to the largest degree possible, I’ve come to the realization that I may not match every feature that Google has to offer, and that’s all right by me. I’ll try to replace a feature completely if I can with an open alternative. If it doesn’t exist or it’s in a form that is incomplete, I’ll attempt to bring it to parity with a Google feature. And if I can’t do that, then I’ll simply learn to live without. Personal privacy and freedom are far more important than convenience with chains attached.

I started looking for a substitute to web-based Google Maps. There’s been a substitute out there for a long time, Open Street Map. Tonight I navigated over to SWITCH2OSM and clicked on the link that led to a single page, showing step-by-step how to install the OSM tools and bring them up on an Ubuntu system. The OSM tools can be installed as a series of packages on Ubuntu version 12.04 (LTS) and higher. My Samsung R580 is running 13.10. By following the very clear directions on that page I was able to install and start my own OSM map server. The only problem I ran into was self-inflicted: I’d installed nginx for an earlier project and forgot it was running. The last stage in installing the OSM tools is to restart the Apache web server as a service. That restart failed because the HTTP port was already being used by nginx. I uninstalled nginx and restarted the Apache service by hand, and everything started to work. Since then I’ve been poking at it and pulling down some of the smaller tiles, starting with the state of Florida. It took less than an hour to get a bare but reasonably functional stand-alone OSM system up. I’ll now be using it to serve tiles to my other notebook for development purposes.

I started looking for a substitute to web-based Google Maps. There’s been a substitute out there for a long time, Open Street Map. Tonight I navigated over to SWITCH2OSM and clicked on the link that led to a single page, showing step-by-step how to install the OSM tools and bring them up on an Ubuntu system. The OSM tools can be installed as a series of packages on Ubuntu version 12.04 (LTS) and higher. My Samsung R580 is running 13.10. By following the very clear directions on that page I was able to install and start my own OSM map server. The only problem I ran into was self-inflicted: I’d installed nginx for an earlier project and forgot it was running. The last stage in installing the OSM tools is to restart the Apache web server as a service. That restart failed because the HTTP port was already being used by nginx. I uninstalled nginx and restarted the Apache service by hand, and everything started to work. Since then I’ve been poking at it and pulling down some of the smaller tiles, starting with the state of Florida. It took less than an hour to get a bare but reasonably functional stand-alone OSM system up. I’ll now be using it to serve tiles to my other notebook for development purposes.

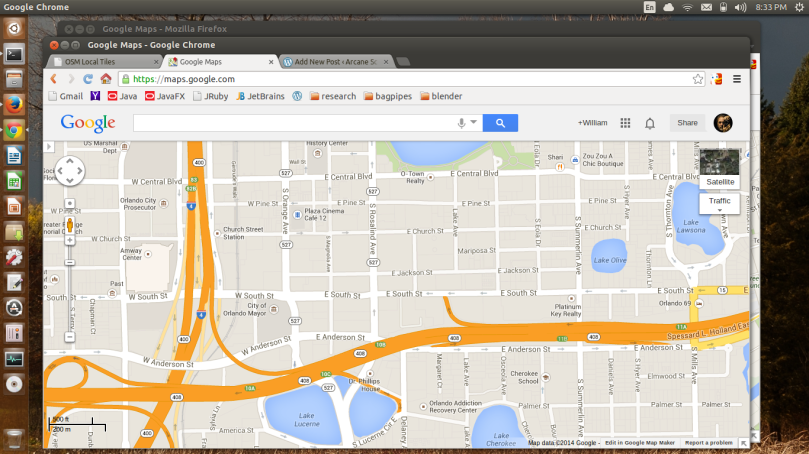

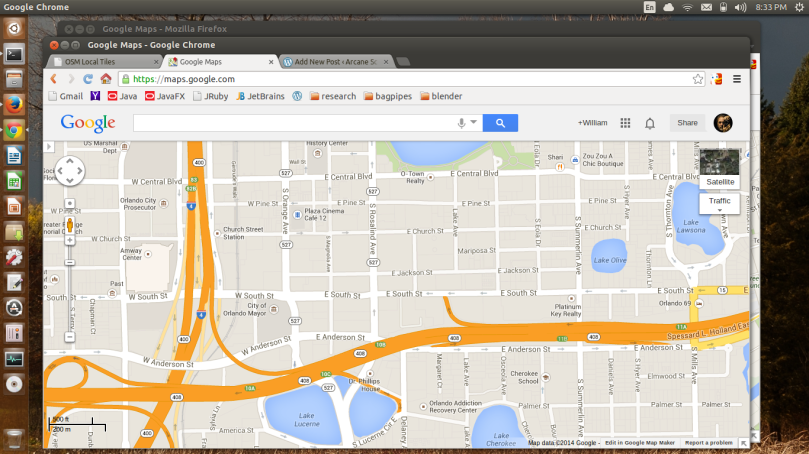

The first two screen shots show Orlando, first with OSM and then with Google Maps. What should be immediately apparent is the lack of controls on the OSM screen. Specifically, there’s no search bar to look for a map location. Since this is my absolute first foray into OSM, I’m not at all concerned. The URL provided is a check-out capability to just see if the whole OSM software stack is working, and it is, with flying colors.

Another difference is visual on the maps themselves. The OSM map has a lot more detail at the same resolution. Levels of detail and how they’re presented are very personal, and once again can be programmatically tweaked in the page itself as well as with some work on the backend. I’m sure there are other open source web pages that can provide the features, and if they aren’t, well, then, dig in and create them and provide them back to the OSM community.

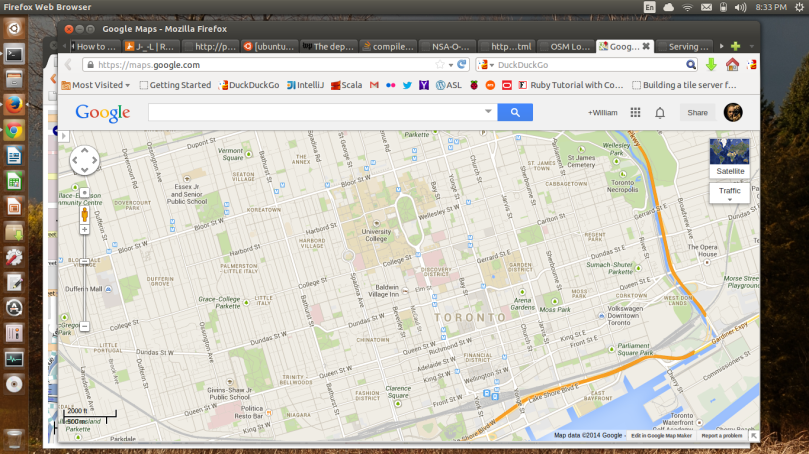

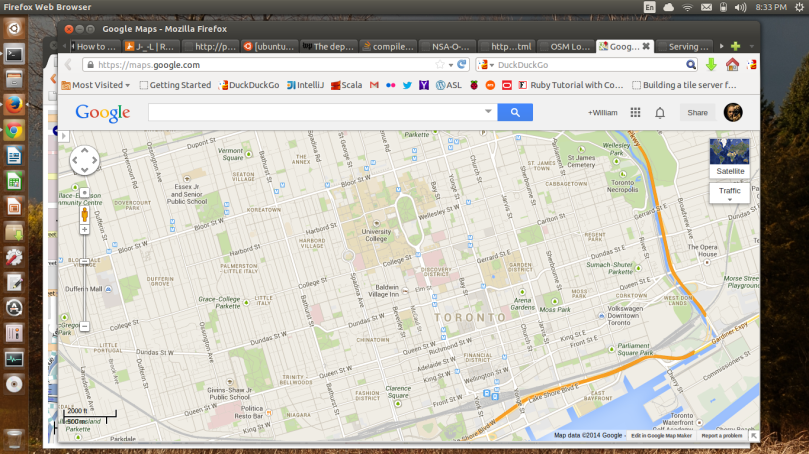

These last two screen shots are of Toronto. I did not download any specific extracts for Toronto or Canada. What you see is what was installed with the initial OSM software stack, and it appears to be quite detailed as-is. Once again the OSM page is missing all the Google Map widgets, and truth be told, I like the clean minimalism of the page. Google’s widgets now encroach too much into the information provided, especially the bar across the top.

I don’t know where I’m going with this, as creating your own map (tile) server can be seen as a bit of overkill. After all, you can go to Open Street Map and just use it. But I’m an inveterate tinkerer; for me it’s interesting to look beneath the “surface” and see how it all works, and even make your own changes, just for the hell of it. It’s all open and inviting.

The corners of the internet devoted to anything new coming from the digital camera makers has been heating up to a fever pitch over the imminent release of Fujifilm’s latest, the X-T1. It’s Fujifilm’s newest entry using their 16MP X-Trans II APS-C sized sensor. This time a Fujifilm X camera is cast as a faux SLR. Except there is no reflex mirror to reflect light from the lens into a pentaprism and out the back eyepiece. It’s all electronic, including the EVF you squint through. The size and shape of the hump is a sop to the corner of the enthusiast market who have become enamored of the retro look in modern digital cameras, in the hope they’ll be more willing to pony up the $1,300 to $1,800 Fujifilm is rumored it wants to ask just for the body. I’m sure there’ll be plenty of takers, especially in the fan-boy quarters of Fujifilm land.

The corners of the internet devoted to anything new coming from the digital camera makers has been heating up to a fever pitch over the imminent release of Fujifilm’s latest, the X-T1. It’s Fujifilm’s newest entry using their 16MP X-Trans II APS-C sized sensor. This time a Fujifilm X camera is cast as a faux SLR. Except there is no reflex mirror to reflect light from the lens into a pentaprism and out the back eyepiece. It’s all electronic, including the EVF you squint through. The size and shape of the hump is a sop to the corner of the enthusiast market who have become enamored of the retro look in modern digital cameras, in the hope they’ll be more willing to pony up the $1,300 to $1,800 Fujifilm is rumored it wants to ask just for the body. I’m sure there’ll be plenty of takers, especially in the fan-boy quarters of Fujifilm land. I’ve grown increasingly desensitized to these continual rapid fire releases of new camera gear from all the makers, including my own brand of preference, Olympus. I got what I wanted and needed well over a year ago with the Olympus E-M5. No need for me to go get an E-P5 or the very latest, the E-M1.

I’ve grown increasingly desensitized to these continual rapid fire releases of new camera gear from all the makers, including my own brand of preference, Olympus. I got what I wanted and needed well over a year ago with the Olympus E-M5. No need for me to go get an E-P5 or the very latest, the E-M1.

You must be logged in to post a comment.