Spend enough time online at any of the photography forums and you’re going to run across stories, usually every quarter, about the declining sale of interchangeable lens cameras (ILCs) that include DSLR and mirrorless. The reasons offered are numerous, but the two biggest reasons as I see them are cost, coupled with how quickly new iterations of the same camera are marketed.

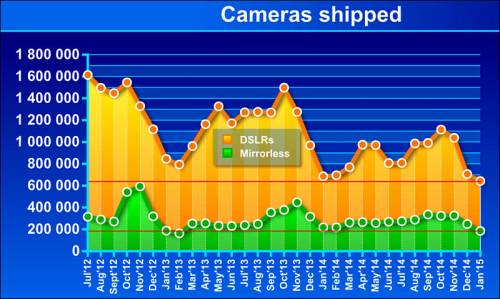

The chart just above is from a website called Personal View and is derived from CIPA (Camera & Imaging Products Association) data. The chart shows both the monthly volatility of the ILC market, as well as a long-term steady downward growth in units shiped. Even someone as stalwart as Thom Hogan uses the chart when he talks about the continuing decline of camera sales. Thom has an interesting article, published in May 2013 (How Steep Was the Decline?), comparing the equivalent rapid sales decline in film bodies with digital. A key fact from this article is that the peak year for digital sales was 2010.

It’s my personal opinion that the reason for the decline of ILCs is due to the very high cost if purchasing any of the cameras, specifically the bodies, coupled with the yearly introduction of ever newer models at the same or higher price point. Consumers, such as myself, pay the top dollar, only to read to their dismay when the next version is released before the new is even properly worn off the current model they own. And they’re told, subtly by the makers and bluntly on the forums, how your current model is immediately obsolete and oh so inferior. Wash, rinse, and repeat.

To a certain extent everyone is right. Your current body is inferior to what always comes next, especially where it truly counts; the sensor and the processor. Technology in those areas, especially the sensor, relentlessly moves forward. The way that the whole industry currently works is, if you want the latest imaging capabilities (more exposure latitude, higher ISO sensitivity without detail destroying noise, etc, etc) then you purchase an entirely new body, instead of just replacing the bits that really matter. Gone are the days of film when you changed film to get a different or better look (or both). When you bought that film body you had a good five or more years, or even longer (such as with Leica) of guaranteed solid use.

It doesn’t take long before a lot of people get tired of it. $1,000 cameras (body with a lens) are expensive discretionary items for lots of people. They justify the expense because they want to document some part of their lives. College kids and twenty-somethings want to document the wilder side of their lives. Marrieds, especially with children, want to document family life. When those kids are grown, then those older parents want to turn around and document their adult children. And therein lies a further complication of the sales problem with the camera industry.

It doesn’t take long before the “real” photographer shows his or her talent in the family. It’s that person who becomes the designated family photographer for the important photos, usually for a number of decades. Everybody else uses their smartphone. The family designated photographer spends the cash for the expensive ILC, along with any number of accessories. That cuts down considerably on the number of units that the camera industry can shift over time, resulting in the huge backlog of older models being sold at discount. The only problem is that marketing keeps saying how the older models are inferior to the current models, not matter how deeply discounted. And so a lot of potential customers who might have bought the older kit on discount wait and the old hardware grows older, increasingly clogging every seller’s inventory.

The camera at the top of this post is an example of introduce high and discount low 12-18 months later. It’s an Olympus E-PL1 with the older 17mm f/2.8 pancake prime. It’s a great camera and the lens does quite well. When the E-PL1 was introduced early 2010 it cost $600 and included the plastic-mount 14-42mm Zuiko kit zoom. When I got it 18 months later it had dropped to $140, body only. I got the prime when it was also discounted at $180, about half its introductory price. The combined camera plus 17mm cost me $320, a little more than half the introductory price. You can’t find the E-PL1 anymore, and the price of the 17mm pancake as actually risen since then. But with that purchase, I learned an important lesson: wait for the price to drop. A lesson taught by Nikon and Sony and Pentax, and even Canon. Wait long enough and the camera you want right now will be affordable. And that puts an even further brake on selling cameras and hurts the manufacturer’s bottom line. Nobody comes out a winner, not the manufacturer or the seller. As for the buyer, low prices like that are a short-term and short sighted gain. In the end manufacturers either stop making cameras because they’re out of business or close to it.

Long term there are no winners.

You must be logged in to post a comment.